Correlation Function Theory¶

Overview¶

In small angle scattering we measure the tendency for probe particles (neutrons, photons, etc) to transfer various amounts of momentum to a sample. The momentum is generally inferred from the scattering angle of probe particles, along with other information about the probe particles (e.g. kinetic energy). Small angle scattering is assumed to be elastic, which allows the momentum transfer to be directly related to a wavelength, and thus a spatial distance. The correlation function represents the scattering intensity in terms of this spatial distance, rather than in terms of momentum transfer.

We can interpret the correlation function in terms of the sample structure by thinking about pairs of points separated by a given displacement. When, on average over the sample, the pairs of points have a high scattering length density, then the correlation function has a large value. Similarly, when the pairs have a low scattering length density, the correlation function is low. More concretely: the correlation function Γ(→r) for vector →r=(x,y,z) is proportional to the pairwise product of scattering length densities for all points separated by the vector (x,y,z) summed over all orientations and locations.

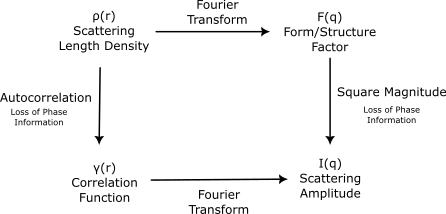

Another way of thinking about the correlation function is as the scattering length density but with phase information removed. As scattering experiments contain no phase information, calculating the correlation function is as close as one can get to calculating the scattering length density from scattering data without incorporating additional information.

The nature of small angle scattering further limits what spatial information can be recovered. Whilst in its most general form the correlation function takes a three dimensional vector input, small angle scattering measurements are limited to one or two dimensions, which in turn limits the amount of information about the correlation function that can be obtained. For this reason, in the correlation function analysis tool we consider various one dimensional projections of the full correlation function, labelled Γ1 and Γ3 .

The Γ1 projection looks at changes in a single direction perpendicular to the beam, with the other directions being averaged. The direction is typically selected by hand from a 2D measurement prior to analysis. Theoretically, the correlation function will be fully recoved as long as the system being looked at is truly one dimensional and properly aligned. However, one must remember the constraints of a small angle scattering experiment, we only measure a small range of momentum transfer, and extrapolate the rest, as such the extrapolation steps must be appropriate for the system. This is in addition to the usual considerations of resolution and systematic measurement error.

The Γ3 projection is motivated by a system of monodisperse, randomly oriented particles in dilute suspension, such that there are no spatial correlations between particles. It is the kind of system described by the Debye equation. Just as is the case with Γ1, as long as one truly has this kind of system, and with caveats about extrapolation and experimental constraints, one should be able to fully recover the correlation function.

Lorentz Correction¶

Lorentz corrections are often used in correlation function analysis. Corfunc uses a Lorentz correction of

In what follows, we assume that appropriate corrections have been made. I(q) here is what would be called I1(q) in Stribeck.

Formal Description¶

More formally, the correlation function is a quantity that arises naturally from calculating the square magnitude of the three dimensional Fourier transform, which is proportional to the scattering amplitude.

where

where dr3 is the volume element (dxdydz).

A couple of algebraic steps will bring us to the correlation function: first, as ρ is real, and the conjugate of eix is e−ix we know that the conjugate of F is given by

meaning that, with some renaming of variables (from r to s and t), we have

With some rearrangement this becomes

and now letting →r=→t−→s and applying the Fourier translation theorem, we can rewrite the above as (note this is not the same →r as before, but a new variable):

Some final reordering of the integration gives

The quantity in square brackets is what is called the correlation function, γ(→r), so:

and it is the quantity that is Fourier transformed (with some appropriate scaling) to get the magnitude of the scattering.

Some useful properties of the Correlation Function¶

As we have mentioned before, the correlation function contains no phase information, mathematically this is the same as saying (1) that its Fourier transform is purely real, or (2) that the correlation function is an even function. The consequence of this is that we can write the Fourier transform of the correlation function using a cosine instead of a complex exponential.

Demonstrating the evenness of the correlation function is easily done by a change of the variable of integration from →s to →u=→s+→r.

and from this we can show that its Fourier transform is real by applying the following to each dimension in turn (shown here in the 1D case for even f(x)).

First, we split the integral into negative and positive x parts:

Let u=−x for the negative part, use the fact that f(−x)=f(x) and recalculate the bounds of integration

Note that u only appears within the integral, so we can rename it to x and recombine it with the positive part. We can also multiply the integral by two and the integrand by two, giving

The fractional part of which is the complex definition of cosine. Applying this definition and using the fact that f(x) is even to restore the original bounds of integration we get

which shows that the Fourier transform is purely real, reflecting the fact that there is no phase information (which would be encoded in the imaginary part).

The \Gamma_1 Projection¶

Consider the Fourier transform of the three dimensional correlation function,

Now let q_z = q_y = 0. The motivation for this is (1) that during small angle scattering q_z is small enough to be neglected, and (2) that we are choosing to measure in one direction of the q_x q_y plane. We assume, without loss of generality, this to be where q_y=0.

This gives us q \cdot r = x q_x, and so the transform becomes

which we can rewrite as

the quantity in the brackets is \Gamma_1(x). That is to say

If we now use the fact that \gamma(\vec{r}) is an even function, we can use the result above to get

The job of Corfunc is now to invert this. The following operation does the job:

We can check this by showing that

Doing this formally requires a fair bit of algebraic legwork, but there is an informal argument that will get us there. First note that we can write it as (hand-waving away the convergence issues)

Then the equation corresponds to the identity function if the integral

is the delta function. This is the case, because cosine functions form an orthogonal basis. When x=y the integral is non-zero, being an integral of the always positive cos^2(qx). Conversely, when x \neq y the integral is zero.

The \Gamma_3 Projection¶

The \Gamma_3 projection is based on spherical symmetry. It’s derivation is essentially that of Debye’s formula

We begin with an expression for the scattered intensity as above

now, we want to average this over all angles, i.e. over all q-vectors of a given length, and we do so in a coordinate system relative to \vec{r}. This is an unobvious choice of coordinate system, but it simplifies things greatly, as in such a coordinate system, the dot product \vec{r}\cdot\vec{q} becomes qr \cos\theta.

For our averaging there is a total of 4\pi steradians in a sphere, giving a leading factor of 1/4\pi.

The integral is constant with with respect to \phi, so drops out as a factor of 2\pi.

and we can adjust the order of integration, noting that because of our choice of coordinate system, \gamma(\vec{r}) is independent of \theta.

Now, we can consider the inner integral specifically, firstly by doing a substitution of u = -\cos\theta. This means that du = \sin\theta d\theta, the interval \theta\in[0,\pi] becomes u\in[1, -1].

which is just an exponential and easily integrated

which by the relationship between complex trigonometric and hyperbolic functions becomes

The leading 2 will cancel the leading 1/2 and the value of I(q) can be seen to be

Note that this object is not dependent on the angular components of \vec{r}, so the integral over \mathbb{R}^3 can be written as

Where \Omega is a solid angle element. Letting

we have, finally,

In corfunc we don’t invert this directly, but do so via \Gamma_1

Relationship between \Gamma_1 and \Gamma_3¶

Internally, Corfunc calculates \Gamma_3 from \Gamma_1. Let’s now look at how we can get one from the other, starting with \Gamma_3.

First, multiply by x

Now take the derivative with respect to x

Which, after expressing in terms of \Gamma_1 gives us the relation we use in corfunc, for calculating \Gamma_3

References¶

Ruland, W. Coll. Polym. Sci. (1977), 255, 417-427

Strobl, G. R.; Schneider, M. J. Polym. Sci. (1980), 18, 1343-1359

Koberstein, J.; Stein R. J. Polym. Sci. Phys. Ed. (1983), 21, 2181-2200

Baltá Calleja, F. J.; Vonk, C. G. X-ray Scattering of Synthetic Poylmers, Elsevier. Amsterdam (1989), 247-251

Baltá Calleja, F. J.; Vonk, C. G. X-ray Scattering of Synthetic Poylmers, Elsevier. Amsterdam (1989), 257-261

Baltá Calleja, F. J.; Vonk, C. G. X-ray Scattering of Synthetic Poylmers, Elsevier. Amsterdam (1989), 260-270

Göschel, U.; Urban, G. Polymer (1995), 36, 3633-3639

Stribeck, N. X-Ray Scattering of Soft Matter, Springer. Berlin (2007), 138-161

Fibre Diffraction Review References (PDF format)